王维仁

香港大學建築系副教授,及王維仁建築研究室主持人,美國建築師學會及香港建築師學會會員,柏克萊加州大學建築碩士,台灣大學土木工程研究所碩士及台灣大學地質系學士。曾任2007年香港建築雙年展策展人,2008年美國麻省理工學院客座副教授,南京大學, 新竹交通大學及同濟大學客座副教授,美國TAC建築師事務所協同主持人。其研究領域為合院建築形態演變,中國寺廟建築形態,傳統及當代中國城市肌理與城市空間。

設計獲獎包括:1999,2001,2002年美國建築師學會設計獎;2001,2002,2003臺灣遠東建築獎;2012及2008年香港綠色建築獎;2009年香港建築師學會獎。作品獲邀參展包括威尼斯建築雙年展,北京建築雙年展,深圳建築城市雙年展,香港建築城市雙年展,成都建築雙年展, 臺北市立美術館等。作品與文章發表於 Stradt Bauwelt,

TA,WA,Dialogue,Domus China,UED 等國內外期刊,包括牛津大學出版社的

<思考再織城市>

;<圍的再生:澳門歷史街區城市肌理研究>,台灣建築以及城市環境設計的專輯<王維仁及其都市合院主義>。

之一: 材料的本真性

谷歌上網查杜邦公司的Corian產品,你會看到:

DuPont™ Corian® Countertops - unlimited possibilities for your home Corian® is the solid surface that gives you the ultimate in freedom of expression and ...;再看中文網站上的關鍵字,就更符合重視實用的中國人:可麗耐®人造石優點耐髒抗污性,符合美國國家衛生基金,容易清潔,堅固耐撞 ,顏色多…是世界第一塊實心面板材料…

兩句英文簡短精要的的”提供家居的無窮可能”以及”給你無盡自由表現的實材表面”,道盡了化工材料科學家無盡的驕傲,也一槍打碎了我們將對藝術品靈光aura和建構詩意的執著。如果本雅明在世,可能也會寫一篇類似”機器復制時代的藝術品”的美學理論,從材料來重新定義作品的本真性 authenticity了。

在Grasshopper和Rhino軟件的支撐下,身處三維曲面造型泛濫的年代,電腦屏幕裡平滑中性的表面是沒有質感的材質。上課時談到設計與材料,我會開玩笑建議不思考建構關系的學生:等到杜邦的材料研發的更好之後,他們的設計就可以一氣呵成的鑄造完成,在光滑平順波浪起伏的未來世界中,很快就可以不用費心思考建構與材質問題了。

不必諱言,在做這個設計的時候,我多少有著樣的心裡障礙,也想用作品辯證一下這個矛盾兩難。

Authenticity of materials

Dupont™ Company introduces its Corian® product in this way on its company homepage: DuPont™ Corian® Countertops - unlimited possibilities for your home Corian® is the solid surface that gives you the ultimate in freedom of expression and ...;The Chinese version of keywords are as follows: Corian® is superior in terms of its stain resistance, easiness to clean and maintain, durability and richness of colors…. is the World’s first solid panel materials. All of which have hit right on the imagination of new possibility in form, as well as Chinese concern over the issue of practicality.

Indeed, the words of “unlimited possibilities for your home” and “ ultimate freedom of expression” have reflected the ultimate pride of material scientists, challenging our obsession over the notion of the aura on artwork and the poetry of tectonic on architecture. If Walter Benjamin were still alive, he was very likely to write another essay about it theorizing the new aesthetic, re-visit the argument in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, redefining the authenticity of artwork in terms of its nature of materials.

With the advent of Grasshopper and Rhino, our era is flooded with three-dimensional curved surfaces – smooth and neutral surfaces shown in computer screen without tangible materials. During my course lecture of design and materials, I sometimes made jokes on my students who paid little attention to architectural relationship: with the further advance of Dupont™ materials, your design could be completed merely through casting, while the issue of material joints and logic of structures are no longer a issue worth contemplating in the future - a future full of smooth and choppy surfaces.

To a certain degree, undoubtedly I certainly have this shadow in my mind during the whole design process, trying to use the design of this furniture work to re-visit this paradox.

之二:木與石

一般認為中國和東亞建築文化選擇木材而非石材作為高貴的建築材料,在於木材本質的生生不息,從大木作舉架開間系統的靈活模距和斗拱鋪作的多元發展,一路到日本園林茶室彎曲的自然樹干,或伊勢神社交替再生的木構築,都是一種有生命而有機的建構發展。因為地心引力和林木生長的競爭與向光性,大料實木大致上都是直線性的,也提供了中國大木作框架體系的理性與笛卡爾坐標的美學邏輯基礎。因此,再眾多垂直相交的木構造節點上,發展出來的不是桁架式的斜撐構建,而是相互疊扣生起出挑的斗拱。

明式家俱的美感除了來自簡練線條與對木材造型柔硬的把握,講究的同時也是小木構件精確而可拆卸的卯榫節點。相對於宋式大木構的直線剛性,明式家俱配合身體動作和視覺變化而調整的輕微曲線,既反映了木材本質直線而又曲折的雙面性,也對家俱的身體功能和材料交接作了恰如其分的反應。

雖然中國也有趙州橋或陵墓地宮的石券和須彌座台基的石刻傳統,在工藝成熟度上明顯的不如羅馬拱廊和水渠,發展出來的石材構建文化和它表達的紀念性,中國人對石材的藝術表現,最高的成就應該是在早期發展出來的玉器文化了。明清供文人貴族案頭把玩的的玉器如翠玉白菜,在精致的工藝裡,表現玉石晶瑩剔透的材質美感;漢朝人流行貼身系帶的玉佩,喜愛的除了是它線條簡潔,虛實正負對比的造型設計,喜愛的更是玉器拙撲溫潤,千萬年在自然山水裡的沉澱醞釀,以及和人體肌膚朝夕撫摸之後,歷久彌新的材料本質。

家居家俱和漢人的玉佩一樣,是和人體朝夕相處互動的物件。中國人不用石材作家居家俱,最多是取鑲嵌大理石面的紋理山水,固然是對木材的文化偏好,也是因為石材缺乏靈活的構建交接。在不自然石材的家居文化裡,杜邦化工不自然的材料交接能力,是否提供了不自然的石材和自然人體互動的契機?

Wood and Stone

Architecture in China and Eastern Asia are mainly built from woods, other than marble, which is largely due to the wood’s essential organic nature – the ability of successively reproduction. From the flexible mold of carpentry work system and the diversified development of wooden bracket, the bent tree trunks near teahouse in Japanese gardens, to the intricate wooden structure of the Ise Grand Shrine, a certain kind of organic structure has flourished vigorously. Due to the geotropism and phototropism nature, tree timbers are largely of linearity, based on which the rationality of China’s carpentry system and the aesthetic logics of Cartesian coordinate could evolve. Therefore, the interlocking wooden brackets, in lieu of diagonal braces, were originated from the perpendicular intersection node of wooden structures.

The beauty of Ming furniture stems largely from its simple flowing lines and the precise control over the wood nature, as well as its accurate design of tiny wooden components and dismountable mortise and tenon. Contrary to Song furniture’s rigidity of big wooden components, Ming furniture boasts its flowing lines, in respond to the movements of bodies and eyesight. Indeed, it has essentially mirrored the duality of woods – linearity and curves, appropriately reacting to the body functionality and material tangibility.

China has its Zhaozhou Bridge and underground palaces as tombs, where the tradition of stone inscription subsists on segmental arches and Sumeru platforms, the techniques, however, were not parallel to that of Roma’s arches, vaults and drains, where the culture of stone architecture was deeply embedded. On the other hand, it is China’s jade culture that fully demonstrates the superior craftsmanship of stone inscription. In Ming and Qing dynasty, those who were educated and rich were keen on the Jade-wares such as Jadeite cabbage, putting them on their reading desks. These Jade-wares represent the exquisite nature of Jade materials, glossy and translucent, echoing the extraordinary craftsmanship. While people in Han dynasty were fond of jade pendants, due to its design of simple lines and shape of Yin-yang contrast. It is also due to essential attributes of jade materials – moist and smooth, embraced and nurtured by the mountains and rivers for millions of years. Moreover, jade materials become even more moist and smooth after possessors have kept their jade pendants close to their skins for years.

Home furniture, similar to the jade pendants of Han dynasty, is the object that accompanies human bodies day and night. Chinese people have seldom used stones to make furniture. Marbles were used merely to decorate the surface of wooden furniture, since the vain on marbles somehow resembles the patterns of landscape. The fact is that Chinese people are culturally inclined to use woods materials. Also, traditional stone materials were enable to have structural joints as flexible as woods.

In the home culture of unnatural stone materials, will there be any opportunity for human bodies to interact with unnatural stone materials in a new mode, with DuPont™ materials’ capability of perfect non-connection?

之三:洞天與家居

道家說的別有洞天,就是山中地底的仙界,相信有三十六洞天和七十二福地,相互連通的洞穴分布在中國的山水地理中,很多五岳真形圖裡描繪的山形,是和洞天不可分割的形式整體。歷代畫家一再描繪的米芾拜石圖,說明了文人對山石文化的癡迷,和文人山水意識的相互強化。文人戀石不但取其山形的奇, 更講究洞石的空間穿透與層次,而明代園林裡,造園師們對洞石的著迷,除了是微觀宇宙的美感,也是道家對洞天的想像。洞天裡的光影景深和對深遠的想像,除了它的文化傳統意涵,也是建築設計裡關鍵的空間經驗, 或者說是現象學式的知覺體會。

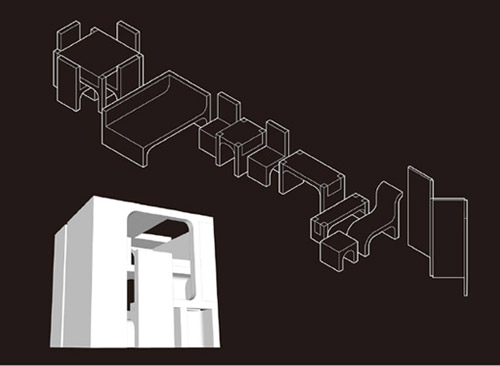

不自然的家居是一個不自然組構的洞天,以不自然的家俱實體構建疊加,形塑成不自然洞天的挖鑿空間,展現光影深遠的虛體空間。由類型學開展出來的家俱形態:桌-椅-丌-凳-榻-台-屛,都是不自然石材與的家居文化以及人體肌膚的互動, 而它們組合成的兩米立方的空間,也正容納了高密度城市極小尺度的,吃喝睡臥的基本家居生活空間: 一個不自然的城市洞天。

Grottoes and home

Taoism says “Bie You Dong Tian(別有洞天)” (literally means there exists a place of unique beauty beyond), which believes in the existence of immortal world in mountains or under ground. In the immortal world, there were thirty-six grottoes (洞天) and seventy-two auspicious lands (福地). The interconnected grottoes were imbedded in China’s landscapes, integrating with the mountain shapes depicted in paintings of Taoism sacred mountains. Across history, generations of Chinese painters have kept depicting about Mi Shi worship stones (米芾拜石), showing Chinese intellectuals’ obsession of mountain stones and the evolution of landscape idealism. Intellectuals’ obsession of stones was not only linked to the unique shapes of mountain stones, but also linked to those stones in grottoes, echoing the depth of space. Garden designers of Ming-dynasty, for instance, were especially interested in stones, keen on the aesthetic experience of micro universe and the imagination of Taoism grottoes. The imagination of light, shadow and depth has mirrored the ideology of Chinese traditional culture. Indeed, it has also inspired the architects in terms of special experience, or cognitive experience of phenomenology.

The unnatural home is a set of unnatural structured grottoes (洞天), made of unnatural furniture, which is built upon on another, indicating an unreal space with light and shadow, depth and distance. The unnatural furniture was evolved based on typology – desk, chair, table, stool, couch, platform and panel. In the home culture of unnatural stones, stone furniture interacts intimately with human bodies. Yet the furniture also built up a 2*2*2 cube, where the minimum living space could be fitted. Eating, drinking, sleeping and lying are arranged in the unit living space, and ultimately an unnatural city grotto is created.

白沙灣海水浴場遊客中心

白沙灣海水浴場遊客中心 香港嶺南大學社區學院

香港嶺南大學社區學院 杭州西溪濕地藝術村

杭州西溪濕地藝術村